awm, on 2012-September-27, 23:25, said:

awm, on 2012-September-27, 23:25, said:

Everything you wrote after this was unnecessary This is the whole problem. If only there was an institution that was capable of printing money and injecting it into the economy to prop up aggregate demand. That would be free.

Oh wait, there is, they just aren't doing a very good job.

Fiscal policy works, but governments aren't very good at actually doing it. Monetary policy works better because it spreads the extra money out around the economy and avoids the distortions that are typical when governments try to increase their spending rapidly. Sensible infrastructure investment takes years of planning, for example. If you want to hire more teachers you first have to train more teachers. Possibly build more teacher training colleges etc.

The only real insight needed to understand nominal shocks, is that "prices clear markets". In the real world, everyone one is prepared to buy things at some price, and we are never so far out of whack in production that there is not a price that clears inventories. If people arent buying something, it means that the price is wrong. If you make it cheaper, more people will buy it. If this happens to the whole economy at once, we call it a nominal shock, and the response should be to change the price of money until people are buying stuff again. The purpose of money is to facilitate economic activity, you should print the amount that maximises economic activity. Since the value of a dollar is basically (All output)/(All dollars spent = NGDP), we see that nominal shocks (changes in NGDP) are really changes in the price of money. So change it back.

If you want to know why NGDP fell, well that is a more difficult question, but the why is not too important in determining the correct policy response. I think the best explanation of why it fell is provided by the collapse of the market in CDO's. There was a market with a daily volume in the trillions of dollars, and then there wasnt. Since items that can be exchanged for cash at face value are money, this represented a collapse in the money supply, and this fed through into a collapse in NGDP. If you prefer to think in terms of inflation, this represented a severe deflationary shock. Deflation makes debt harder to handle, and this is basically what drove the banks under. Then the banks started raising liquidity by sucking cash out of what you would call the `real' economy. Thus the deflationary shock in finance was translated into the real economy. The ideal early response is a cash injection into the banks, in return for a share of the profits later, before the deflationary pressure pushed out into the real economy. Now, the ideal response is to inject cash into the real economy, via QE, which will eventually feed into the banking sector and fill up the gaping hole in their liquidity.

Finally, the reason it is still going on, is that wages are downards sticky. For example, the chicago teachers did not say that `look, mr Rahm, we realise inflation has undershot, and that our pay now buys 8% more consumption than it was supposed to when we agreed our last pay deal five years ago, and so we should start our negotations with a 8% pay cut.'. Of course, consumption is what matters. Low inflation is crippling chicago's budget, as all its public employees are getting paid more than their negotiations were meant to pay them. If you look at the chicago balance sheet, it will look like revenues are down, but of course this is just the money illusion. Real GDP has not changed nearly as much as revenue projections would suggest, as money is just worth more now.

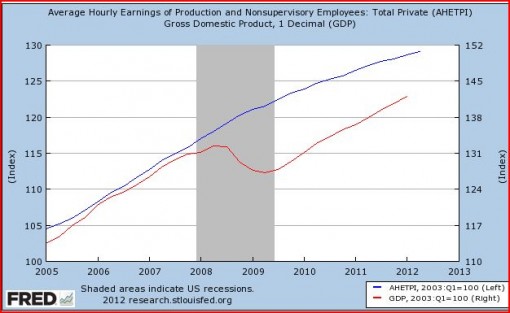

Here is a nice graph of sticky wages:

The blue line is average hourly wages, the red line is RGDP, both in 2003$. That tiny down turn in the blue line's gradient is the effect of "wage renormalisation".

At least now that the Fed is taking steps to do suitable policy, there is a pretty good chance that the red line will start to catch up to the red line over the coming months.

Help

Help